It’s a deceptively simple question that determines the success of your entire workout: How long should you rest in between sets?

There are several training variables we can adjust to get the most out of our program. We may carefully manipulate the load we’re lifting, the intensity of each set, and our total weekly volume in order to get closer to a particular outcome like increasing muscle size or getting stronger on a particular lift. For many lifters, rest times between sets is often an afterthought, yet choosing to rest too little or too long could mean leaving potential strength and muscle gains on the table.

This article takes a science based approach to rest periods in order to potentially maximize performance in a given exercise session, which repeated over time, could yield better improvements in strength and muscle gain.

Note: For more information and nuance on this topic, check out episode #275 on the Barbell Medicine Podcast by clicking here.

Why Do We Need to Rest Between Sets?

Before we discuss how much to rest, we need to know why we have to. The purpose of a rest period is to dissipate fatigue that accumulates during the set that was just performed. Any set of an exercise produces some amount of fatigue. Some sets are capable of producing more fatigue, or different types of fatigue, than others. For example, performing a set of 12 reps of biceps curls to an RPE of 7 may produce a different amount and type of fatigue than a set of 3 deadlifts at an RPE of 9. Further, you may need to rest shorter or longer after each of those efforts before doing another set of biceps curls or deadlifts.

The Relationship Between Rest, Intensity, Volume, and Fatigue

Fatigue represents the subjective experience of a number of exercise-induced changes in an individual such as muscular soreness, muscular damage, tiredness, etc. that can lead to reduced force production. There is also likely to be some controversy in this definition of fatigue, as others define muscle fatigue as purely a decrease in force production potential, which can be measured by a strength test. To use the same exercise examples as above, your force production potential immediately after completing a triple on the deadlift at an RPE of 9 or a set of 12 on biceps curls at an RPE of 7 will be less than it was before you did the set.

Neurologically, the production of muscular force has both central and peripheral components. Because of this, as does fatigue. In this view, muscle fatigue represents the performance difference between before and after the intervention – a hard set – and is divided into central and peripheral components.

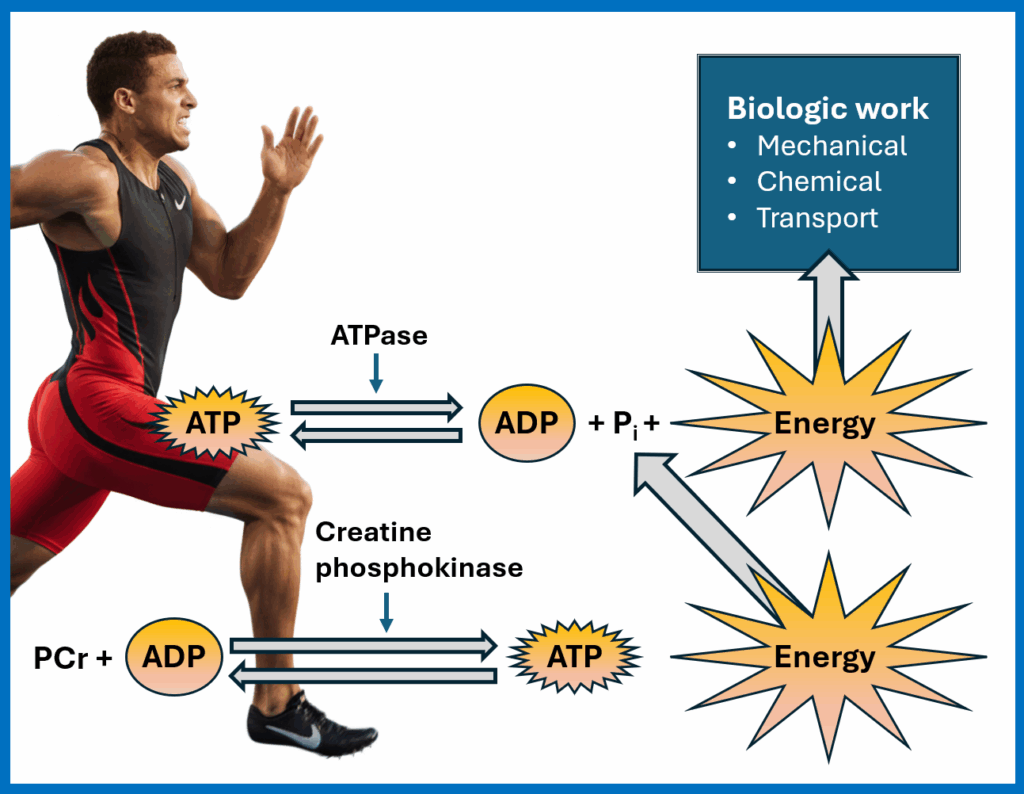

Peripheral fatigue is produced by changes at or downstream to the neuromuscular junction – where the nerve meets the muscle. The signal that gets the muscle to contract is still preserved, but the contraction produces less force. Peripheral fatigue can be caused by things like muscle damage, the accumulation of metabolic byproducts like lactate and hydrogen ions that occurs with repeated muscle contraction, and and the depletion of energy substrates like ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and PCr (phosphocreatine).

On the other end, central fatigue stems from changes upstream to the neuromuscular junction – the brain, the spinal cord, and the nerves supplying the muscles. This type of fatigue results in a smaller than normal signal being sent to the muscle, thereby causing the muscle to produce less force. A number of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine are involved. This is one of the potential mechanisms by which methylphenidate – the active drug in ritalin or concerta – is thought to increase physical performance. Other mechanisms include some of the metabolic byproducts discussed above as well as mechanical tension itself stimulating group III and IV afferent nerves that can inhibit muscle contraction signaling.2

Both central and peripheral factors can contribute to the experience of fatigue. As far as the body of literature that is currently available, it seems to focus mostly on energy availability and the removal of metabolic byproducts as factors causing peripheral fatigue. There is limited data at this time on the factors affecting central fatigue. So, let’s focus on the peripheral components to attempt to answer the question of why we rest.

What Happens During Rest Intervals? (Energy system recovery, ATP, and PCr)

From an energy standpoint in strength and hypertrophy training, the two biggest players here are thought to be ATP and PCr.

The molecule ATP stores energy in its phosphate bonds. The “tri” in adenosine triphosphate means that this molecule has 3 phosphate groups. When we use an ATP molecule for energy, we clip one of these phosphates off and the breaking of that bond releases usable energy. This breakdown of ATP leaves behind its constituent components adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). Skeletal muscles then transform this released chemical energy into mechanical energy causing a muscle contraction.

ATP is a relatively heavy molecule, so we do not store a lot of it in our muscles. Instead, we store other molecules and have several bioenergetic pathways to replenish ATP just as rapidly as we use it up. Because we are pretty good at replenishing ATP, the decrease in ATP levels during resistance training is usually small or statistically insignificant. Multiple studies have shown this, suggesting that ATP is being almost entirely regenerated during exercise and we probably don’t need to rest a lot in order to replenish our ATP stores. Because of the relatively quick regeneration, our limited ATP stores are back to 100% after about 3 to 5 minutes of rest following strenuous exercise.

So, we aren’t necessarily resting to restore ATP as that seems to happen almost instantly. PCr, another molecule stored in the muscle in higher quantities than ATP, is used to regenerate ATP very rapidly. PCr helps turn that molecule ADP back to usable ATP. PCr levels in the muscle plummet during a hard set or anaerobic effort, with some studies showing up to an 80% drop in PCr levels during a single, short effort of less than 45 seconds. These same studies show it takes about 8 minutes to fully replenish PCr levels back to pre-exercise conditions.3

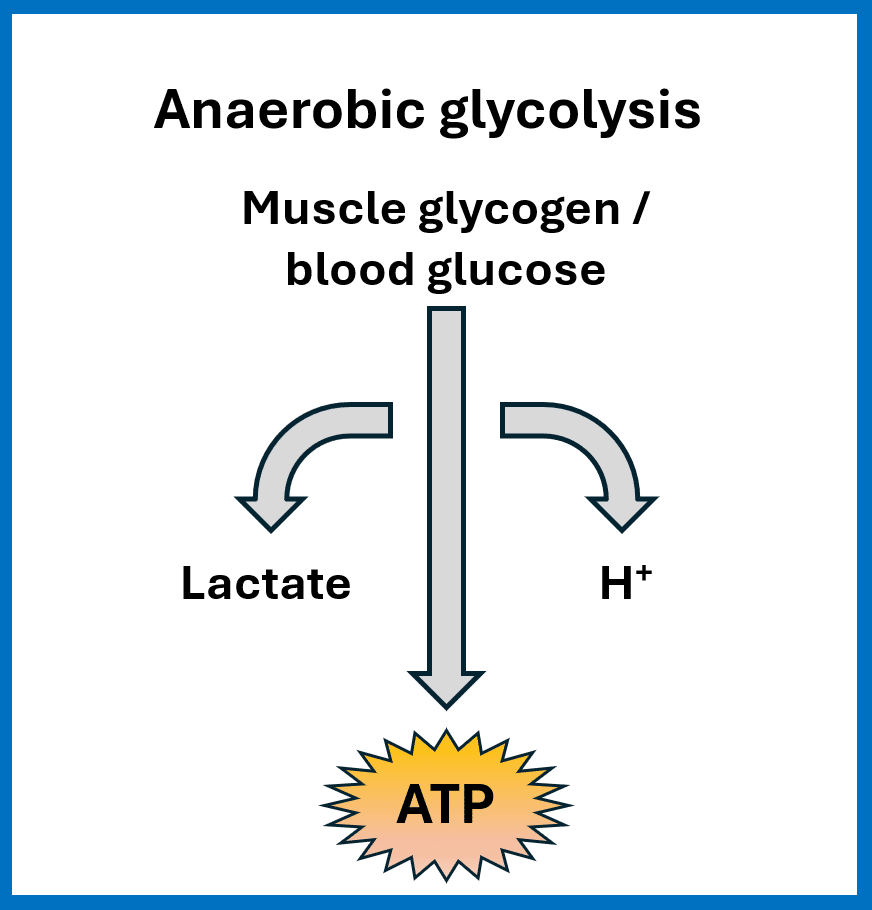

This interaction between ATP and PCr is not the only supplier of energy during hard sets or anaerobic efforts. The other contributor to muscle energy during lifting is the breakdown of muscle glycogen, the stored form of carbohydrates in our muscles. This process is called glycogenolysis and the energy system acting here is termed anaerobic glycolysis. While ATP and PCr are doing their thing, muscle glycogen breakdown is also contributing to ATP regeneration to fuel muscle contraction. This process of anaerobic glycolysis does two things that contribute to peripheral fatigue. First, it creates lactate and hydrogen ions as a byproduct which makes the muscle a little more acidic thus impairing calcium release within the muscle and impairing contraction. Second, it’s depleting the stored carbohydrates we have in our muscles – muscle glycogen.

While these factors from the breakdown of glycogen can play a role in peripheral fatigue, it usually isn’t as large of a factor for short term sets. This process seems to peak at about 45 seconds of output. So, doing 400m repeats on a track would certainly generate fatigue from this mechanism. For sets that take a long time – high reps, drop sets, extended tempo work, and so on – this is probably a factor. But what about fatigue from short sets? A set of 3 reps on the squat at an RPE of 8 would not likely generate a large amount of fatigue from these bioenergetic mechanisms.

Current evidence suggests that the combined decrease in phosphocreatine (PCr) levels along with an increase in acidity from hydrogen ions following anaerobic glycolysis are two major mechanisms of action contributing to peripheral fatigue. As the set goes on, PCr depletion, glycogen depletion, increasing acidity, activation of group III and IV nerves, and so on likely all contribute to the experience of fatigue.

While this review of exercise physiology was fun, there are a lot of factors involved in the experience of fatigue, and it’s hard to associate specific factors with a particular type of fatigue, central or peripheral.4

What we do know about fatigue is that it happens as the demands of a task become greater and greater. So, using more weight, doing more sets, using more muscle mass, and getting closer to failure all increase this experience of fatigue. Anyone who has ever done a near maximal effort set or maximal effort sprint has experienced this. The more work done generates more fatigue.

While this discussion of fatigue is important, this is an article about rest periods. And, the point of the rest period is to manage the accumulation of fatigue in a training session.

The point of a rest period is to allow the trainee to train with enough intensity to achieve their desired adaptation from training.

This is going to be an important theme throughout the rest of the article. If rest periods are shortened too much, results suffer because people aren’t able to generate enough force or accumulate enough mechanical tension. If rest periods are lengthened too much, results may also suffer because people aren’t able to do enough exercise due to time constraints.

As you may have guessed, there may be subtle differences in the amounts of rest that are optimal for different goals; strength or hypertrophy, for example.

Let’s dive a bit into the research on different rest period protocols and their effect on performance.

How Long Should Rest Periods Be For Strength Training?

What drives the gains in strength that come from training? A combination of evidence and practical training and coaching experience tell us that the accumulation of training volume at an appropriate intensity drives our strength gains. In order to train this way we need to be able to continuously produce high levels of force throughout our entire workout.

If a rest period is too short, the trainee’s performance may dwindle on subsequent sets thus limiting the volume accumulated and the intensity used. So, if you rest too short the weight on the bar, the reps and sets performed, and the RPE level may be lower as compared to what you could accomplish using a longer rest period. If a rest period is too long, the training session may take too long and people may even lose interest making very long rest periods impractical. Both of these situations may be less than ideal for driving the desired adaptations.

To maximize strength gains, we recommend a rest period of between 2-5 minutes. Let’s take a look at how this shakes out in the research.

A recent meta-analysis compared the results of 27 studies that evaluated 416 adults, mostly men, with 1 year of training or more. They examined the effects of traditional sets, like doing 8 reps, resting a few minutes, then doing another set of 8 reps, and so on as compared to something called rest redistribution. Rest redistribution is when an individual takes rests between reps of a set and then cuts down their rest period between sets. This is sort of like a cluster set. For example, you may do 5 reps, rest for 15-20 seconds, and then do 3 more reps, and then rest a full 90 seconds before your next set of 8 total reps that may have a rest somewhere in that 8 rep period.

So, what did this meta-analysis find? When using rest redistribution, the weights being lifted had higher velocities, less velocity loss during the set, generated less lactate, and were rated at lower RPE’s by the lifters. When the rest periods between sets were extended – so cluster sets as described above with the same amount of rest between sets as a traditional set – the RPE and velocity loss tended to be even less.

This speaks to possibly better recovery between sets; as the performance seemed to be better on subsequent sets as indicated by less velocity loss and lower RPE’s.

The first takeaway here is that more rest can allow people to lift the same volume with less fatigue. Additionally, with emerging data showing that greater loss in velocities during a set tend to produce worse outcomes compared to a modest loss, the thought would be to rest long enough between sets to maintain your exertion level to keep bar speed from dropping too much and RPE from climbing too high.

The second takeaway is that adding more total rest time can increase the duration of the training session, perhaps affecting adherence and the amount of volume that can be done. We know that training volume is very important to training outcomes like strength, size, and cardiorespiratory fitness, so we can’t rest for too long either. Unfortunately, this meta-analysis didn’t compare strength or size outcomes between cluster sets, rest redistribution, and traditional sets, so we don’t know which one worked better for what we really care about — how much rest do we need to optimize training performance, training outcomes, and time spent training. For that, we’ll need to dig into some more data.5

As far as strength is concerned, a 2017 meta analysis looked at 23 studies that all lasted at least 4-weeks and tested strength before and after the training intervention in 491 subjects. The subjects were mostly young men and half of the studies were in trained individuals while the other half was in untrained folks.6

In the trained subject studies, the longer rest intervals tended to maximize improvements in strength. One of the included studies compared rest periods of 30s, 90s, and 180s in 33 trained men to see how it affected their 1RM squat. All groups lifted 4 times per week for 5 weeks, alternating sessions of squats, push presses, bench presses, and some accessory work with clean pulls, power snatches, and rows, each done for 5 sets of 10 at a 10RM. The 180s group increased their squat 1RM by 7% whereas the 30s group increased their 1RM squat by only 2%. Interestingly, the 90 second group increased their squat 6%, despite requiring half the rest time as the 180s group.7

Another study in 36 men compared rest periods of 1, 3 and 5 minutes to each of 3 groups during a 16 week training program where they alternated upper and lower body days over 4 training sessions per week. In one session, they’d go heavy in the 4 to 6 rep max range. In the other session, they’d go a bit lighter in the 8 to 10 rep max range. They tested the 1RM bench press and leg press in each group at the end of the 16 weeks. A very important finding here, they did not all do the same volume, as the reps completed were affected by the rest periods used.

For example, the 5 minute rest group did about 40% more volume than the 1 minute group and 15% more than the 3-minute group. Due to this volume difference, the results are somewhat predictable.

For the leg press, the 1 min rest group improved by 22%, whereas the 3 min group improved 34%, and the 5 minute group improved 42%. For the bench press, the 1 minute group improved by 7%, the 3 minute group by 13% and the 5 minute group by 11%. The bench press surprisingly did not show a significant difference in 1RM between the 3 and 5 minute groups, but the relationship between 1 minute of rest and the other groups are pretty clear.8

A few of the other studies reviewed in the meta analysis compared longer rest periods of 4 and 5 minutes to shorter ones of 2 minutes to see if there were any differences. In general, the studies looking at longer rest periods showed that the individuals were able to lift heavier weights during the sets and do more reps as well. The only negative, as mentioned earlier, is that the 5 minute rest period group couldn’t do as much volume in the time allotted for training. At the end of 6 months in this particular study, there were no significant differences in strength or hypertrophy between the group resting 5 minutes vs 2 minutes.9

Finally, two more recent studies looked at the volume and velocity loss with short versus long rest intervals. Compared with rest periods of less than 2 minutes, longer rest periods consistently resulted in greater training volumes on average.10 Similarly, compared to resting only 1 minute in between 3 heavy sets of 5 on the squat or bench press, resting 3 or 5 minutes resulted in greater bar speed and less velocity loss on sets 2 and 3. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in velocity or velocity loss between resting 3 and 5 minutes.11

Taken together with the other data collected in the meta analysis, it seems pretty clear that rest periods longer than 2 to 3 minutes are better for strength development in trained individuals as it seems to allow for the accumulation of more volume-load (sets x reps x load). It’s less clear if extending rest periods from 3 to 5 minutes or longer actually improves strength long-term, as rest periods of this length may compromise the ability to do enough volume in a workout. In untrained individuals, the rest interval doesn’t seem to matter much based on the available data. In both untrained and trained individuals, shorter rest periods tends to make the sets in a session get closer to muscular failure and raise the RPE and discomfort of the session, which should be considered in programming.

Overall, strength gain seems to be maximized with longer rest periods in the 3 to 5 minute range for compound exercises. As someone becomes more trained, they may not require as long of rest periods before they can do the next set, thereby allowing them to do more training in the same amount of time. Longer rest periods of 5 minutes or greater may increase performance in the short term, but they can also limit the amount of training people can do in a session, ultimately limiting long-term development. If you’re in the final stages of prepping for a meet or 1RM test, resting longer than 5 minutes may be beneficial. Since volume should be rather low at this point, it’s probably not going to cause any issues with getting the training done either. Outside of that unique situation, there may not be a need for extending the rest period beyond 5 minutes.

On to the next outcome of concern, hypertrophy.

How Long Should Rest Periods Be For Hypertrophy?

While there is definitely overlap in the training for strength and hypertrophy, there are some nuances in the modifiable training variables of a program that can be adjusted to optimize one versus the other.

Hypertrophy is defined in most studies as an increase in total mass of a muscle, or a muscle’s cross sectional area (CSA). This is driven primarily by mechanical tension from lifting weights, which then drives increases in muscle protein synthesis. If we want to maximize the amount of mechanical tension our muscles can produce, then we need to preserve our force producing capabilities. Much like with strength training, when rest periods are too short fatigue may prevent us from producing high levels of force. If rest periods are too long, however, the workout may just be impractical from a time perspective thus limiting the amount of volume a trainee can accumulate.

For hypertrophy outcomes, we recommend rest periods of between 2-4 minutes.

Resistance training relies heavily on anaerobic pathways to create energy (ATP) for the muscles, which results in the buildup of metabolic byproducts such as hydrogen ions, inorganic phosphate, lactate, and others. Research has continually shown that these metabolic byproducts are associated with muscle hypertrophy, though it is not clear they’re directly causal.

Anytime the muscles are contracting during resistance training, they’re producing these metabolites, making it hard to determine whether metabolites contribute to hypertrophy or if it’s just the mechanical force from muscular contractions. Based on the present data, it appears the majority of muscular hypertrophy is caused by mechanical signals, whereas metabolites may have an indirect role, if any at all.

Nonetheless, it’s been hypothesized that people focusing on gaining muscle size might do better with shorter rest periods in an effort to increase this metabolic stress, thereby increasing an anabolic signal to the muscle. Of course, if these shorter rest periods negatively impact the volume-load used for a training session, it could limit total mechanical tension. Let’s take a look at the research on this.

In one study, 16 men did 4 sets of leg press and 4 sets of leg extensions at 75% of their 1RM to failure. One group rested a minute between sets and the other rested 5 minutes between sets. Biopsies of the leg were taken after the workout, which showed that muscle protein synthesis increased 152% in the 5 minute group, whereas it only went up 76% in the 1-minute group.12

Another mechanistic study looked at men training with either 2 or 5 minutes of rest over 6 months to see if the shorter rest periods produced greater increases in lactate or hormones associated with muscle growth. The levels of growth hormone, testosterone, and cortisol were measured across the 6 months. This was a crossover study, where each subject trained with 2 minute rest periods for 3 months and then 5 minute rest periods for the other 3 months to see if there were differences within the individual with different training programs. In this study, there were no differences in blood lactate, growth hormone, testosterone levels, or cortisol levels with the different rest periods. Both groups increased strength and hypertrophy, but there were no differences based on the rest periods.9

Looking just at these mechanisms of hypertrophy like muscle protein synthesis levels and hormone levels can be misleading, so let’s talk about real world hypertrophy outcomes in subjects.

A 2016 study had 23 men train 3 times per week for 8 weeks where they did 3 sets of 8 to 12 reps for 7 exercises per session, resting for either 1 or 3 minutes. At the end of 8-weeks, the group resting 3 minutes had done more volume, lifted heavier weights, and had significantly more growth in their biceps, triceps, and quadriceps muscles. They also had double the improvement in their 1RM squat, up 15% compared to 7.5% in the 1-minute rest group. Those resting 3 minutes improved their 1RM bench by 12.7%, compared to 4% in the 1-minute group. Of note, the researchers tested the subjects’ muscular endurance by having them do 50% of their 1RM bench and squat to failure. Those resting 3 minutes improved their performance by 10% more than the short rest group.13

In a meta analysis of 6 studies looking at the effect of rest period length on hypertrophy, mostly in untrained men lifting 4 times per week for 8 weeks or so, almost all of the results favored the longer rest period for driving more hypertrophy. Of note, the short rest periods were usually between 20 to 60 seconds and the long rest periods were up to 4 minutes in length.14

Overall, the data on rest periods and hypertrophy seems to highlight a similar relationship to that seen in strength training. Longer rest periods seem to lead to improvements in muscle gain, likely because people can do more volume and possibly because less fatigue is being generated. There’s a point of diminishing returns though, where even longer rest periods – say 5 minutes – don’t necessarily do better than something more modest like 3 minutes. There may also be an effect specific to exercise selection – with exercises using heavier loads and more muscle mass like squats and bench presses likely doing better with more rest. Isolation, or single-joint movements, that moves relatively less muscle mass and lower absolute loads on the other hand may do better with shorter rest periods of 2 to 3 minutes. Again, the amount of rest people need between sets to maintain volume (reps per set) and exertion level (RPE or RIR) is likely trainable. As people get more and more fit, they may be able to decrease their rest periods a bit without much of an issue.

Other Factors Influencing Your Ideal Rest Time

Exercise Type

Different exercise types may require more rest than others. Exercises using more weight, more volume in the form of reps and sets, and more muscle mass can generate more fatigue thus requiring more rest. For example, many people will report feeling less fatigue from a set of biceps curls as compared to a set of 10 heavy squats. The biceps muscle is simply less muscle mass than the combined mass of the quadriceps, gluteals, and back so the rest required here would be lower. We still recommend to rest within the 2-4 minute range for hypertrophy or the 2-5 minute range for strength but where you fall in that recommendation may vary based on the exercise chosen.

For lower intensity, single-joint or isolation exercises like lateral raises, triceps pushdowns, or calf raises it may be more appropriate to rest closer to that 2 minute mark where as for higher intensity, compound movements like squats, deadlifts, and bench presses more maximizing that rest period is recommended.

Training Experience

A lifter’s training experience may also affect their required rest times. One of the adaptations the body makes to training is increased efficiency and capacity of the energy systems that supply muscle contraction. That being said, the absolute loads and relative intensities being used by novice lifters and advanced lifters could be vastly different. So, of course, there is some nuance here in applying rest periods to lifters with different experience levels.

Novice Lifters

New lifters may require more rest than advanced trainees because their ATP/PCr and anaerobic glycolytic systems are not as adept at regenerating ATP. They may have smaller PCr and glycogen stores and reduced buffering capacity of lactate and hydrogen ions as compared to advanced trainees. This may mean that they may need to rest longer than a trained individual for bioenergetic purposes.15 All of that said, newer exercisers will usually use smaller absolute loads and train with a lower relative intensity – RPE. This may mean that newer lifters can get away with slightly less rest because the fatigue they are generating is less. We recommend novice lifters to still abide by the recommendations of 2-4 minutes for hypertrophy training and 2-5 minutes for strength training; but where they fall within that window has to do with them feeling as if they are ready for another set.

Advanced Lifters

Advanced lifters have spent a long time conditioning their ATP/PCr and anaerobic glycolytic energy system so they have made adaptations that lead to increased efficiency and capacity of these systems. They will have larger ATP, PCr, and glycogen stores as compared to untrained athletes. They will also have greater activity of the enzymes involved in these systems like phosphofructokinase and creatine kinase making these energy systems more efficient.16 Advanced lifters, however, will likely be using larger absolute loads and may train at higher relative intensities, or RPEs which may require longer rest periods. We recommend advanced lifters also to abide by the recommendations of 2-4 minutes for hypertrophy training and 2-5 minutes for strength training. A subtle difference here may be for strength athletes peaking for a meet when training volume is very low may rest for greater than 5 minutes between singles at very high percentages of 1RM and high RPEs. In this unique scenario, the problem of not having enough time to complete the required volume doesn’t exist as volume is typically quite low during this period of training.

Short on time? Reduce Your Training Time with Supersets

A superset is when two different exercises are completed back-to-back with minimal rest. In the situation where there is limited time to complete a workout, one option is to use a superset. If done properly, a superset can reduce total training time, while still maintaining total training volume and average intensity. With supersets you can use your rest time to train a totally different muscle group.

Supersets come in three major flavors, agonist-agonist, agonist-antagonist, and alternate-peripheral.

Agonist-Agonist supersets are where an individual trains the same muscle group twice in a row with two exercises like doing bench press then flies. This is traditionally used in body building to enhance the fatigue in the local musculature – trying to take the pecs “past” failure. This approach typically produces higher degrees of muscle damage and greater reductions in both training volume and force production, particularly on the second exercise of the superset.

When compared to splitting them up and just doing straight sets, the reduction in volume tends to produce worse outcomes related to hypertrophy. If total volume is maintained, then hypertrophy outcomes are likely to be similar.

However, strength outcomes still appear to be worse since loading and force production are compromised. To summarize, agonist-agonist supersets can be used for hypertrophy if total volume is maintained, but they are not generally a good option for strength.

Agonist-antagonist supersets are where two exercises that train opposing muscle groups are paired together, such as bench press and then a row. This approach can be very useful for reducing time in training without compromising outcomes, as training volume and force production appear to be maintained because there is little overlapping fatigue from the opposing muscle groups. When you’re performing a bench press, and then you perform a row, and then you rest two minutes, you’re not only getting the two minutes of rest for your pecs, anterior deltoids, and triceps. Rather, you’re also resting the active muscles in the bench press during the rows, and the active muscles in the rows during the bench press.

The major application for agonist-antagonist supersets would be hypertrophy, as a lot of volume can be performed for a given amount of time. It’s okay for strength as well, but probably not a great option for maximal strength development as components of central fatigue may impact your force production.

Alternate-peripheral supersets are where two completely unrelated exercises are paired together – a squat and overhead press. When looking at alternate-peripheral supersets that are not taken to failure, e.g. to RPE 6-8 for example, the training volume, peak loads, and force production tend to be maintained.

This can be a useful approach for general strength development, but probably isn’t best for powerlifting- or max-strength specific training. The overall cardiorespiratory demand of doing two heavy compound exercises, especially if you’re strong, which train a lot of the muscle groups in the body, can cause some loss of volume and force production, which would be undesirable if someone is trying to pull out all the stops for strength development.17

Implementing and Adjusting Rest Periods in Your Program

To gain the most strength:

- Rest periods of 2-5 minutes produce better results as compared to shorter rest periods due to the accumulation of more volume at the appropriate exertion level.

- Shorter rest periods may impact the total volume able to be performed due to intraset fatigue and longer rest periods may impact the total volume performed due to time constraints.

- Compound exercises like squats, deadlifts, and bench presses that move more total muscle mass and typically move larger absolute loads may require rest periods that are longer, 4-5 minutes as compared to single joint exercises like biceps curls or lateral raises that may require only 2-3 minutes of rest.

- Rest periods of greater than 5 minutes may benefit performance in the short term, which may be appropriate for strength athletes peaking for a meet or a 1RM test.

To gain the most muscle:

- Rest periods of 2-4 minutes produce better results as compared to shorter or longer rest periods due to the accumulation of volume at the appropriate exertion level.

- Shorter rest periods, while possibly increasing metabolic stress, may negatively impact the accumulation of volume which limits mechanical tension. Longer rest periods may negatively impact the amount of volume that can be accumulated in a session due to time constraints.

- Compound exercises like squats, deadlifts, and bench presses that move more total muscle mass and typically move larger absolute loads may require rest periods that are longer, 4-5 minutes as compared to single joint exercises like biceps curls or lateral raises that may require only 2-3 minutes of rest.

References

- Baird, M. F., Graham, S. M., Baker, J. S., & Bickerstaff, G. F. (2012). Creatine-kinase- and exercise-related muscle damage implications for muscle performance and recovery. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2012, 960363. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/960363

- Zając, A., Chalimoniuk, M., Maszczyk, A., Gołaś, A., & Lngfort, J. (2015). Central and Peripheral Fatigue During Resistance Exercise – A Critical Review. Journal of human kinetics, 49, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2015-0118

- McMahon, S., & Jenkins, D. (2002). Factors affecting the rate of phosphocreatine resynthesis following intense exercise. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 32(12), 761–784. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200232120-00002

- Wan, J. J., Qin, Z., Wang, P. Y., Sun, Y., & Liu, X. (2017). Muscle fatigue: general understanding and treatment. Experimental & molecular medicine, 49(10), e384. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.194

- Jukic, I., Ramos, A. G., Helms, E. R., McGuigan, M. R., & Tufano, J. J. (2020). Acute Effects of Cluster and Rest Redistribution Set Structures on Mechanical, Metabolic, and Perceptual Fatigue During and After Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 50(12), 2209–2236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01344-2

- Grgic, J., Schoenfeld, B.J., Skrepnik, M. et al. Effects of Rest Interval Duration in Resistance Training on Measures of Muscular Strength: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 48, 137–151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0788-x

- Robinson, J. M., Stone, M. H., Johnson, R. L., Penland, C. M., Warren, B. J., & Lewis, R. D. (1995). Effects of different weight training exercise/rest intervals on strength, power, and high intensity exercise endurance. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 9(4), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1519/00124278-199511000-00002

- de Salles, B. F., Simão, R., Miranda, H., Bottaro, M., Fontana, F., & Willardson, J. M. (2010). Strength increases in upper and lower body are larger with longer inter-set rest intervals in trained men. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 13(4), 429–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2009.08.002

- Ahtiainen, J. P., Pakarinen, A., Alen, M., Kraemer, W. J., & Häkkinen, K. (2005). Short vs. long rest period between the sets in hypertrophic resistance training: influence on muscle strength, size, and hormonal adaptations in trained men. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 19(3), 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1519/15604.1

- Santana, W. J., Silva, E. M., & Silva, G. P. (2023). Recovery between sets in strength training: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. https://www.scielo.br/j/rbme/a/Y9vYkwhHhbzKcKNSG9Ft85s/?format=pdf&lang=en

- González-Hernández, J. M., Jimenez-Reyes, P., Janicijevic, D., Tufano, J. J., Marquez, G., & Garcia-Ramos, A. (2023). Effect of different interset rest intervals on mean velocity during the squat and bench press exercises. Sports biomechanics, 22(7), 834–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2020.1766102

- McKendry, J., Pérez-López, A., McLeod, M., Luo, D., Dent, J. R., Smeuninx, B., Yu, J., Taylor, A. E., Philp, A., & Breen, L. (2016). Short inter-set rest blunts resistance exercise-induced increases in myofibrillar protein synthesis and intracellular signalling in young males. Experimental physiology, 101(7), 866–882. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP085647

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., Schnaiter, J. A., Bond-Williams, K. E., Carter, A. S., Ross, C. L., Just, B. L., Henselmans, M., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 30(7), 1805–1812. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272

- Grgic, J., Lazinica, B., Mikulic, P., Krieger, J. W., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2017). The effects of short versus long inter-set rest intervals in resistance training on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(8), 983–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2017.1340524

- Ross, A., Leveritt, M., & Riek, S. (2001). Neural influences on sprint running: training adaptations and acute responses. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 31(6), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200131060-00002

- Kaczor, J. J., Ziolkowski, W., Popinigis, J., & Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2005). Anaerobic and aerobic enzyme activities in human skeletal muscle from children and adults. Pediatric research, 57(3), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1203/01.PDR.0000150799.77094.DE

- Zhang, X., Weakley, J., Li, H., Li, Z., & García-Ramos, A. (2025). Superset Versus Traditional Resistance Training Prescriptions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Exploring Acute and Chronic Effects on Mechanical, Metabolic, and Perceptual Variables. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 55(4), 953–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-025-02176-8