Obesity is often reduced to a single number: weight on the scale. The reality of this condition, however, is far more complex. In healthcare, numbers can guide many decisions. Blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels all guide decision making between a patient and their physician as they assess risk and manage disease. For decades, the Body Mass Index (BMI) has been the standard tool for assessing obesity-related health risks, despite its well-known limitations. For years, critics have decried BMI for not taking into account muscle mass in its calculation. But, an even greater flaw lies in its inability to capture where fat is stored in the body, a factor strongly linked to disease outcomes. A newer tool, the Body Roundness Index (BRI), is gaining traction for doing exactly that, potentially offering a clearer picture of obesity and its health consequences. Could this be a more accurate way to assess obesity and predict disease risk? Will BRI replace BMI?

Obesity is a complex, chronic disease influenced by multiple factors. It is currently defined as a condition characterized by an excessive accumulation of body fat that leads to abnormal functioning of the fat, or adipose tissue, as well as abnormal physical forces on the body due to the excess fat mass. Together, these mechanisms result in harmful metabolic, biomechanical, and psychosocial health consequences such as diabetes, heart disease, chronic musculoskeletal pain, depression, and more.

As with any other disease process, the ability to identify and diagnose obesity is important to properly treat people with obesity. As it currently stands, there are several ways to assess obesity and body fat levels to determine the risk an individual has for obesity related illnesses.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), hydrostatic (underwater) weighing, and air displacement plethysmography (Bod-Pod) methods can assess an individual’s body fat levels. However, these tests are expensive and inaccessible for most individuals making them an impractical choice to assess for obesity levels and re-assess to track progress. Going one step further, these methods become increasingly impractical to apply to large populations of people for research or public health policy informing purposes.

For this reason, simple screening tools that require only a few measurements and a calculation have gained popularity due to their ability to diagnose people with obesity without the need of specialized equipment or a significant financial or time burden. This makes an assessment of obesity take seconds in a doctor’s office or research lab.

Most people are familiar with one of these screening tools; Body Mass Index, or BMI. While BMI has its pros and cons, it has had staying power as a screening tool due to its ease of use. To calculate BMI you only need to know someone’s height, measured in meters (m), and weight, measured in kilograms (kg). One of the most common, and important, critiques of BMI is that it does not take into account where the weight is located. Is the extra weight in the muscle of the quads and biceps or around the waistline as fat tissue?

In recent years a new screening tool to assess health risk related to obesity has emerged known as the Body Roundness Index. The Body Roundness Index takes into account where the excess weight is located, as opposed to just assessing whether or not it is there. Because of this advantage over BMI, many are calling for it to replace BMI. But, should it?

In this article we’ll discuss what the Body Roundness Index is, how and why it was developed, how to measure it, the latest science on this new tool, and opine about whether or not it should replace BMI.

You can also listen to our podcast discussion on BRI: Body Roundness Index – Episode #316 of the Barbell Medicine Podcast

Why should we assess obesity by more than just weight?

As stated above, obesity is a complex and multifactorial disease. We view excess body fat or adipose tissue as a sign of the underlying disease of obesity. This underlying disease results in the person achieving energy balance at a higher-than-healthy body fat level. Ideally, appetite and food-related behaviors would match people’s energy and nutrition needs. For example, as energy stores (body fat) increases, appetite and energy intake are suppressed, spontaneous physical activity increases, and vice versa. However, in the setting of obesity, these signals are often mismatched.

The rates of those with overweight and obesity are increasing in every single country in the world. Globally, over 2 billion adults are overweight and over 650 million have obesity. It’s predicted that this number will soon grow to over 1 billion adults with obesity worldwide.1,2

The body mass index (BMI) aims to screen for obesity, which is a disease characterized by excess body fat. While there are other tools to assess an individual’s body fat, like those mentioned above, these assessments typically do not account for where the excess fat is located.

Body Mass Index, or BMI, replaced a previous calculation known as Ideal Body Weight. It is a quick calculation that could be done for anyone while visiting a doctor’s office and also for research purposes when attempting to quantify health for large populations of people. All that is needed to calculate BMI is a person’s height measured in meters (m) and weight in kilograms (kg).

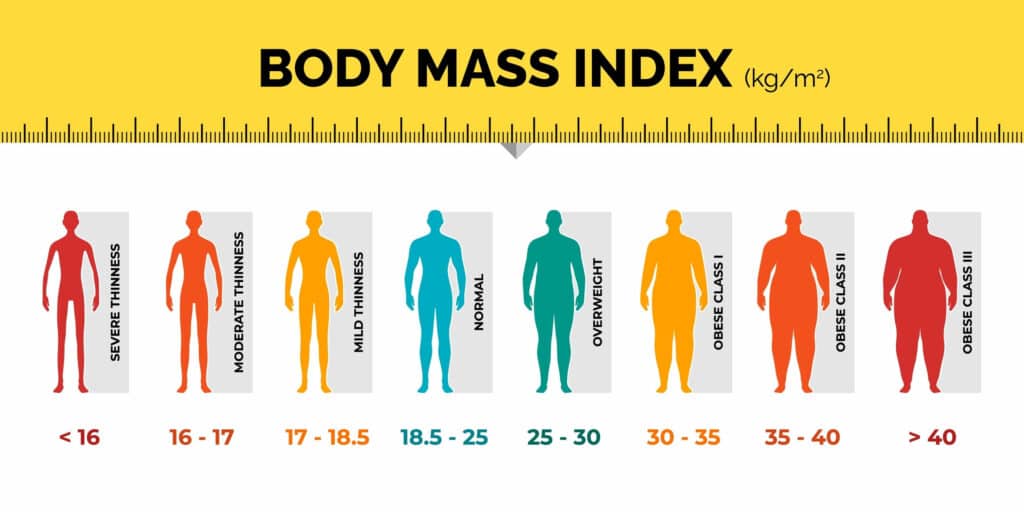

For screening and diagnostic purposes, a BMI of less-than 18.5 corresponds to an individual at risk for being underweight, whereas a BMI of 25 is used for overweight, and a BMI of 30 or higher is used for obesity. The current guidelines also recognize that individuals of different ethnic backgrounds may require different cutoff points to screen for health risks due to excess body fat. For example, it is suggested that a BMI cutoff point value of ≥23 kg/m2 should be used in the screening and confirmation of excess adiposity in South Asian, Southeast Asian, and East Asian adults.

As a screening and diagnostic tool, BMI is just okay.

Many critics of BMI claim that it overdiagnoses obesity in people that are heavily muscled. Being that only 24% of the US population meets the minimum physical activity guidelines for both conditioning and strength training, this is likely not a widespread issue.3 In fact, BMI has a specificity of 95-99%.31 This means that it has very few false positives. As far as medical tests go, that is very good. This means that 95-99% of people with a BMI of greater than 30 truly do have obesity. On the other hand, BMI is not a very sensitive test. When a test is 100% sensitive, it catches everyone who has the condition being tested for. We don’t see this with BMI. For example, there are people who have a BMI of less than 30 but are still considered to be carrying too much body fat. Assessments of BMI have found that it has a sensitivity of less than 36% for men and 49% of women. So BMI actually misses almost half of people who are carrying too much body fat.

Therefore, the biggest problem with using BMI alone is that it tends to miss far more individuals who carry excess body fat, rather than inappropriately diagnosing those who are actually too muscular. To go one step further, BMI does not take into account where the bodyfat is located.

So, why does the location of body fat even matter? Fat is fat, right?

Location, Location, Location: Fat location can predict health risk

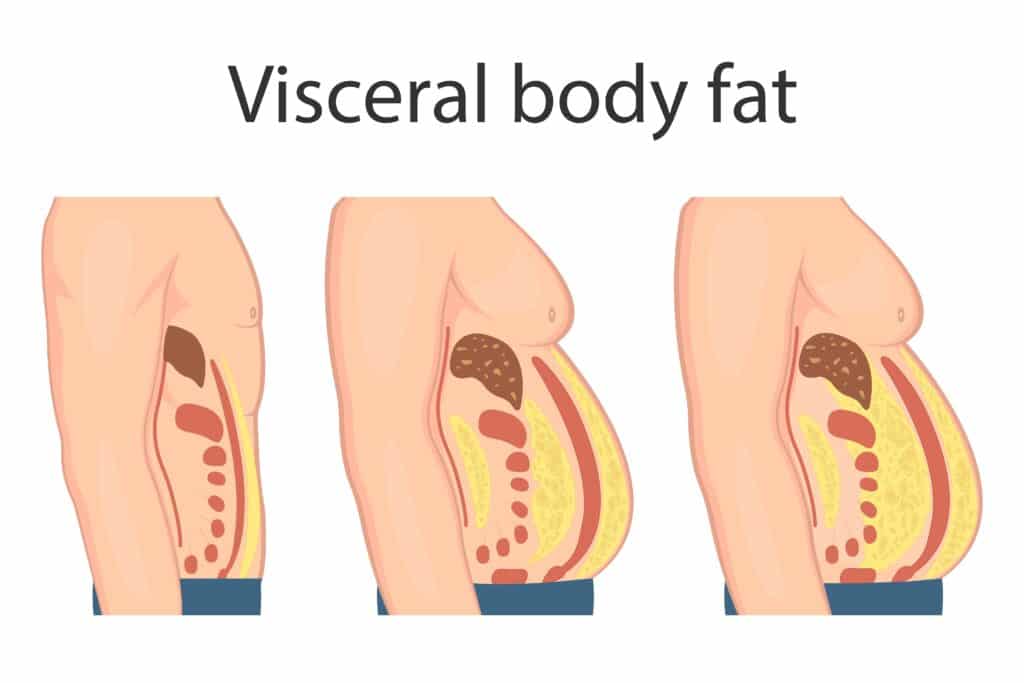

Generally speaking, humans distribute their body fat in two major sites within the body. Body fat can be stored subcutaneously, or under the skin, or viscerally in the abdomen around the organs. The relative amounts of body fat stored in a particular location varies significantly among individuals based on sex, age, race, activity level, the total amount of body fat, and even certain medications.

Excess visceral fat in the abdomen is recognized as an established risk factor that is strongly correlated with cardiovascular events like heart attacks and stroke, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality. In contrast, the same level of body fat located elsewhere, such as the arms, legs, and buttocks, does not produce the same risk. There is a growing consensus that visceral fat is much more dangerous to health than subcutaneous fat, since it entails more risk for diseases.6 Abdominal fat in particular produces a number of inflammatory hormones called adipokines that are involved in obesity-related chronic diseases.10

As we already discussed, BMI only takes into account a person’s height and weight, but not where the excess fat is located when classifying obesity levels. To overcome these limitations, most guidelines recommend also obtaining a waist circumference measurement to gather information about where an individual’s body fat is distributed. This seems to more accurately determine an individual’s risk of health problems from carrying too much body fat.8

To measure your waist circumference, place a measuring tape directly against the skin in a circle around the abdomen at the level of the navel. Ensure the measuring tape is flat and even, not high or low on one side or another, and make sure it is not pressing into the skin. This measurement only takes a moment and can add to BMI to get a better picture of health risk related to obesity.

Not only is this assessment convenient, but it is also very accurate. Waist circumference measurements are highly correlated to the amount of abdominal fat in both men and women as measured by MRI and CT scans.44,25 Being that MRI and CT scans are expensive and inaccessible for many, doctor assisted or self-measured waist circumference measurements present a great opportunity to get a clearer picture of health risk. After instruction, self-measured waist circumference values are both accurate and reproducible, so people should feel empowered to do these assessments on their own.45

For an individual with a BMI between 23 and 35, it is recommended to also obtain a waist circumference to see where this weight is located. A waist circumference of at least 102 centimeters, or approximately 40 inches, in men indicates abdominal obesity, though a lower cut off of 94 cm, or 37 inches, has been suggested. In women, a waist circumference of 88 centimeters, or approximately 35 inches, indicates abdominal obesity, with a lower target of 80 cm, or 32 inches, being suggested.11,5

Generally speaking, combining BMI and waist circumference together do a pretty good job of identifying those at risk of disease from carrying too much body fat, outperforming metrics like waist to hip ratio, waist to height ratio, and BMI alone.16 This leads to people having two scores assessing obesity, BMI and a waist circumference. Deciding what these numbers mean alone and then together presented some diagnostic challenges.

In an attempt to simplify this process, researchers tried to combine BMI and waist circumference into one screening tool that computes a single value which could subsequently be used to diagnose obesity.17

This led to the eventual creation of the relatively new screening tool, the Body Roundness Index.

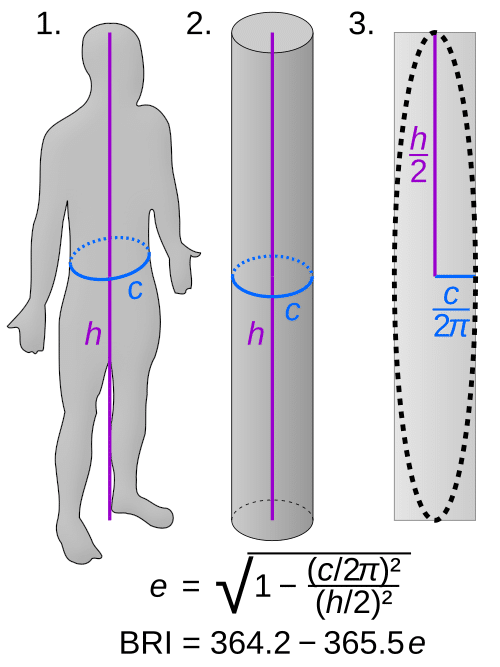

The body roundness index aims to model an individual’s body shape to predict their body composition and body fat distribution in an effort to better characterize an individual’s health risk from excess body fat.18 Theoretically, assuming the shape of the body as an ellipse with the long axis being represented by height and the short axis by waist circumference, the body roundness index can be calculated as the eccentricity of this ellipse via human modeling on a scale from 1 to 20, with 1 being a more narrow and 20 being more round. As you can see below, as waist circumference increases, the ellipse becomes more round.

The variables used in the calculation include: an individual’s height, age, weight, sex, race, and waist circumference. This makes for an accurate picture of disease risk from excess adipose tissue as all of these things tend to influence both body composition and body fat distribution. The formula is quite complex, but the linked Body Roundness Index calculator will take care of the math for you. Calculate your Body Roundness Index here.

In the general population, the average body roundness index is 5.62, which has gone up over the past 20 years following the rise in obesity. The body roundness index was higher in Mexican American individuals, followed by non-hispanic black individuals, then non-hispanic white individuals. A similar trend was also observed based on education, with those obtaining a college education having the lowest body roundness index.

A data set on over 30,000 adults in the United states shows an interesting relationship between body roundness index and health risk. Body roundness index scores of 4.5 to 5.5 are correlated with the lowest risk of mortality from all causes. Interestingly, body roundness scores of less than 3.4 have a 25% increased risk of mortality from all causes. Research suggests that a very low score may indicate sarcopenia, or muscle loss, frailty, or malnutrition.43 Those with a body roundness index score of greater than 6.9 have a 50% increased risk of mortality from all causes, which is attributed to excess body fat.38,21

Thanks to the Body Roundness Index, we now have a new screening tool that assesses health risk based not only on excess adipose tissue but also where that tissue is located all packaged into one number.

With all of this in mind, it seems that the Body Roundness Index is a more accurate screening tool than what has been used in the past. Research has demonstrated that it appears to work better than either BMI or waist circumference alone when it comes to predicting risk of heart disease, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, reduced kidney function, and even all cause mortality. This is especially true in populations where the standard BMI cutoffs, e.g., 25 for overweight and 30 for obesity, are already known to be off, such as those of Asian descent and/or elderly individuals.22, 28, 32, 30, 46

So, should Body Roundness Index be the new BMI? Should we just throw BMI away and forget it ever existed?

Should BRI replace BMI?

While the Body Roundness Index is a more accurate tool, how we use it will determine whether or not it has any impact on actually managing obesity.

There are a few potential positives to widespread adoption of the Body Roundness Index and areas of future research that could improve its impact on obesity management.

First, the positives. As already detailed above it appears to be a better screening tool than BMI and waist circumference alone. If doctors, public health officials, or researchers are going to be making decisions about a person’s health or public policy it certainly makes sense to have the best possible data to work with.

In addition, it gives one value that correlates to health risk as opposed to two. While this may not seem like that big of a deal, consider the implications of seeing hundreds of patients a week or working with data sets of tens of thousands of people. For the health system and research system as a whole, working with one number makes sense from an efficiency standpoint.

Lastly, using Body Roundness Index circumvents the negative association most folks have with BMI. Even people outside of the health and fitness space may have negative beliefs or feelings towards BMI which could turn them away from even considering monitoring it with their health care provider. Using the Body Roundness Index instead could facilitate conversations around the topic of obesity in the doctor’s office in a more productive manner which could lead to better outcomes.

Will BRI improve the management of obesity?

Widespread adoption of the Body Roundness Index could simplify the diagnosis and quantification of obesity related health risk which could lead to better management of the disease. If the Body Roundness Index replaced BMI entirely, it would guarantee that people’s waist circumference and ethnicity are taken into consideration when attempting to quantify obesity related disease risk. Future research will hopefully tell us what amount of change in body roundness index leads to health risk changes and over what time frame. Overall, the Body Roundness Index seems like a very useful and accurate tool based on a solid scientific foundation.

References

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Boutari C, Mantzoros CS. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: as its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism. 2022 Aug;133:155217. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2022.155217. Epub 2022 May 15. PMID: 35584732; PMCID: PMC9107388.

- Bhattacharyya, M., Miller, L. E., Miller, A. L., Bhattacharyya, R., & Herbert, W. G. (2024). Disparities in adherence to physical activity guidelines among US adults: A population-based study. Medicine, 103(36), e39539. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000039539

- Ciemins EL, Joshi V, Cuddeback JK, Kushner RF, Horn DB, Garvey WT. Diagnosing Obesity as a First Step to Weight Loss: An Observational Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020 Dec;28(12):2305-2309. doi: 10.1002/oby.22954. Epub 2020 Oct 7. PMID: 33029901; PMCID: PMC7756722.

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, Nadolsky K, Pessah-Pollack R, Plodkowski R; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY COMPREHENSIVE CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR MEDICAL CARE OF PATIENTS WITH OBESITY. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jul;22 Suppl 3:1-203. doi: 10.4158/EP161365.GL. Epub 2016 May 24. PMID: 27219496.

- Gruzdeva O, Borodkina D, Uchasova E, Dyleva Y, Barbarash O. Localization of fat depots and cardiovascular risk. Lipids Health Dis. 2018 Sep 15;17(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0856-8. PMID: 30219068; PMCID: PMC6138918.

- Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Thomas RJ, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korinek J, Allison TG, Batsis JA, Sert-Kuniyoshi FH, Lopez-Jimenez F. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008 Jun;32(6):959-66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. Epub 2008 Feb 19. PMID: 18283284; PMCID: PMC2877506.

- Mulligan AA, Lentjes MAH, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Changes in waist circumference and risk of all-cause and CVD mortality: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019 Oct 28;19(1):238. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1223-z. PMID: 31660867; PMCID: PMC6819575.

- Abate N, Garg A, Peshock RM, Stray-Gundersen J, Grundy SM. Relationships of generalized and regional adiposity to insulin sensitivity in men. J Clin Invest. 1995 Jul;96(1):88-98. doi: 10.1172/JCI118083. PMID: 7615840; PMCID: PMC185176.

- Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D. The molecular mechanisms of obesity paradox. Cardiovasc Res. 2017 Jul 1;113(9):1074-1086. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx106. PMID: 28549096

- Jensen MD. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S102-38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. Epub 2013 Nov 12. Erratum in: Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S139-40. PMID: 24222017; PMCID: PMC5819889.

- Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Thomas RJ, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korinek J, Allison TG, Batsis JA, Sert-Kuniyoshi FH, Lopez-Jimenez F. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008 Jun;32(6):959-66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. Epub 2008 Feb 19. PMID: 18283284; PMCID: PMC2877506.Sommer I, Teufer B, Szelag M, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Titscher V, Klerings I, Gartlehner G. The performance of anthropometric tools to determine obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 29;10(1):12699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69498-7. PMID: 32728050; PMCID: PMC7391719

- Mulligan AA, Lentjes MAH, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Changes in waist circumference and risk of all-cause and CVD mortality: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019 Oct 28;19(1):238. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1223-z. PMID: 31660867.

- Abate N, Garg A, Peshock RM, Stray-Gundersen J, Grundy SM. Relationships of generalized and regional adiposity to insulin sensitivity in men. J Clin Invest. 1995 Jul;96(1):88-98. doi: 10.1172/JCI118083. PMID: 7615840.

- Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D. The molecular mechanisms of obesity paradox. Cardiovasc Res. 2017 Jul 1;113(9):1074-1086. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx106. PMID: 28549096.sThompson D, Karpe F, Lafontan M, Frayn K. Physical activity and exercise in the regulation of human adipose tissue physiology. Physiol Rev. 2012 Jan;92(1):157-91. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2011. PMID: 2229865Grundy SM, Neeland IJ, Turer AT, Vega GL. Waist circumference as measure of abdominal fat compartments. J Obes. 2013;2013:454285. doi: 10.1155/2013/454285.PMID: 23762536.

- Sommer I, Teufer B, Szelag M, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Titscher V, Klerings I, Gartlehner G. The performance of anthropometric tools to determine obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 29;10(1):12699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69498-7. PMID: 32728050.

- Zhu S, Heshka S, Wang Z, Shen W, Allison DB, Ross R, Heymsfield SB. Combination of BMI and Waist Circumference for Identifying Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Whites. Obes Res. 2004 Apr;12(4):633-45. PMID: 15090631.

- Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, Mueller M, Shen W, Gallagher D, Maeda Y, McDougall A, Peterson CM, Ravussin E, Heymsfield SB. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Nov;21(11):2264-71. doi: 10.1002/oby.20408. Epub 2013 Jun 11. PMID: 23519954; PMCID: PMC3692604.

- https://webfce.com/bri-calculator/

- Zhang X, Ma N, Lin Q, et al. Body Roundness Index and All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415051. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 Zhang X, Ma N, Lin Q, et al. Body Roundness Index and All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415051. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 Rico-Martín S, Calderón-García JF, Sánchez-Rey P, Franco-Antonio C, Martínez Alvarez M, Sánchez Muñoz-Torrero JF. Effectiveness of body roundness index in predicting metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020 Jul;21(7):e13023. doi: 10.1111/obr.13023. Epub 2020 Apr 8. PMID: 32267621.

- Zhou D, Liu X, Huang Y, Feng Y. A nonlinear association between body roundness index and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in general population. Public Health Nutr. 2022 Nov;25(11):3008-3015. doi: 10.1017/S1368980022001768. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35983642; PMCID: PMC9991644.

- Cai X, Song S, Hu J, Zhu Q, Yang W, Hong J, Luo Q, Yao X, Li N. Body roundness index improves the predictive value of cardiovascular disease risk in hypertensive patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a cohort study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2023 Dec 31;45(1):2259132. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2023.2259132. Epub 2023 Oct 8. PMID: 37805984.

- Wu L, Pu H, Zhang M, Hu H, Wan Q. Non-linear relationship between the body roundness index and incident type 2diabetes in Japan: a secondary retrospective analysis. J Transl Med. 2022 Mar 7;20(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03321-x. PMID: 35255926; PMCID: PMC8900386.

- Zhang Y, Gao W, Ren R, Liu Y, Li B, Wang A, Tang X, Yan L, Luo Z, Qin G, Chen L, Wan Q, Gao Z, Wang W, Ning G, Mu Y.Body roundness index is related to the low estimated glomerular filtration rate in Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 28;14:1148662. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1148662. PMID: 37056676; PMCID: PMC10086436.

- Zhu S, Heshka S, Wang Z, Shen W, Allison DB, Ross R, Heymsfield SB. Combination of BMI and Waist Circumference for Identifying Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Whites. Obes Res. 2004 Apr;12(4):633-45. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.73. PMID: 15090631.

- Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, Mueller M, Shen W, Gallagher D, Maeda Y, McDougall A, Peterson CM, Ravussin E, Heymsfield SB. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Nov;21(11):2264-71. doi: 10.1002/oby.20408. Epub 2013 Jun 11. PMID: 23519954; PMCID: PMC3692604.

- https://webfce.com/bri-calculator

- Rico-Martín S, Calderón-García JF, Sánchez-Rey P, Franco-Antonio C, Martínez Alvarez M, Sánchez Muñoz-Torrero JF. Effectiveness of body roundness index in predicting metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020 Jul;21(7):e13023. doi: 10.1111/obr.13023. Epub 2020 Apr 8. PMID: 32267621.

- Wu L, Pu H, Zhang M, Hu H, Wan Q. Non-linear relationship between the body roundness index and incident type 2 diabetes in Japan: a secondary retrospective analysis. J Transl Med. 2022 Mar 7;20(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03321-x. PMID: 35255926; PMCID: PMC8900386.

- Zhang Y, Gao W, Ren R, Liu Y, Li B, Wang A, Tang X, Yan L, Luo Z, Qin G, Chen L, Wan Q, Gao Z, Wang W, Ning G, Mu Y. Body roundness index is related to the low estimated glomerular filtration rate in Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 28;14:1148662. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1148662. PMID: 37056676; PMCID: PMC10086436.

- Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Thomas RJ, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korinek J, Allison TG, Batsis JA, Sert-Kuniyoshi FH, Lopez-Jimenez F. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008 Jun;32(6):959-66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. Epub 2008 Feb 19. PMID: 18283284; PMCID: PMC2877506.

- Mulligan AA, Lentjes MAH, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Changes in waist circumference and risk of all-cause and CVD mortality: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019 Oct 28;19(1):238. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1223-z. PMID: 31660867.

- Abate N, Garg A, Peshock RM, Stray-Gundersen J, Grundy SM. Relationships of generalized and regional adiposity to insulin sensitivity in men. J Clin Invest. 1995 Jul;96(1):88-98. doi: 10.1172/JCI118083. PMID: 7615840.

- Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D. The molecular mechanisms of obesity paradox. Cardiovasc Res. 2017 Jul 1;113(9):1074-1086. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx106. PMID: 28549096.sThompson D, Karpe F, Lafontan M, Frayn K. Physical activity and exercise in the regulation of human adipose tissue physiology. Physiol Rev. 2012 Jan;92(1):157-91. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2011. PMID: 2229865Grundy SM, Neeland IJ, Turer AT, Vega GL. Waist circumference as measure of abdominal fat compartments. J Obes. 2013;2013:454285. doi: 10.1155/2013/454285.PMID: 23762536.

- Sommer I, Teufer B, Szelag M, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Titscher V, Klerings I, Gartlehner G. The performance of anthropometric tools to determine obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 29;10(1):12699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69498-7. PMID: 32728050.

- Zhu S, Heshka S, Wang Z, Shen W, Allison DB, Ross R, Heymsfield SB. Combination of BMI and Waist Circumference for Identifying Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Whites. Obes Res. 2004 Apr;12(4):633-45. PMID: 15090631.

- Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, Mueller M, Shen W, Gallagher D, Maeda Y, McDougall A, Peterson CM, Ravussin E, Heymsfield SB. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Nov;21(11):2264-71. doi: 10.1002/oby.20408. Epub 2013 Jun 11. PMID: 23519954; PMCID: PMC3692604.

- Zhang X, Ma N, Lin Q, et al. Body Roundness Index and All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415051. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 Zhang X, Ma N, Lin Q, et al. Body Roundness Index and All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415051. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 Rico-Martín S, Calderón-García JF, Sánchez-Rey P, Franco-Antonio C, Martínez Alvarez M, Sánchez Muñoz-Torrero JF. Effectiveness of body roundness index in predicting metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020 Jul;21(7):e13023. doi: 10.1111/obr.13023. Epub 2020 Apr 8. PMID: 32267621.

- Zhou D, Liu X, Huang Y, Feng Y. A nonlinear association between body roundness index and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in general population. Public Health Nutr. 2022 Nov;25(11):3008-3015. doi: 10.1017/S1368980022001768. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35983642; PMCID: PMC9991644.

- Cai X, Song S, Hu J, Zhu Q, Yang W, Hong J, Luo Q, Yao X, Li N. Body roundness index improves the predictive value of cardiovascular disease risk in hypertensive patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a cohort study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2023 Dec 31;45(1):2259132. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2023.2259132. Epub 2023 Oct 8. PMID: 37805984

- Wu L, Pu H, Zhang M, Hu H, Wan Q. Non-linear relationship between the body roundness index and incident type 2diabetes in Japan: a secondary retrospective analysis. J Transl Med. 2022 Mar 7;20(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03321-x. PMID: 35255926; PMCID: PMC8900386.

- Zhang Y, Gao W, Ren R, Liu Y, Li B, Wang A, Tang X, Yan L, Luo Z, Qin G, Chen L, Wan Q, Gao Z, Wang W, Ning G, Mu Y.Body roundness index is related to the low estimated glomerular filtration rate in Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 28;14:1148662. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1148662. PMID: 37056676; PMCID: PMC10086436.

- Yang, Y., Shi, X., Wang, X., Huang, S., Xu, J., Xin, C., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Ye, Y., Liu, S., Zhang, W., Lv, M., & Tang, X. (2025). Prognostic effect of body roundness index on all-cause mortality among US older adults. Scientific reports, 15(1), 17843. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02598-4

- Grundy, S. M., Neeland, I. J., Turer, A. T., & Vega, G. L. (2013). Waist circumference as measure of abdominal fat compartments. Journal of obesity, 2013, 454285. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/454285

- Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990 Nov;1(6):466-73. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009. PMID: 2090285.

- Gao, W., Jin, L., Li, D. et al. The association between the body roundness index and the risk of colorectal cancer: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 22, 53 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-023-01814-2