Whether you’ve been working out for years or are just starting, you’ve likely seen the term “progressive overload” billed as a foundational concept in exercise. It’s the magic bullet, the secret sauce, the one universal truth that every coach and trainer agrees is necessary for making progress.

What they don’t agree on, however, is what it actually means.

In our previous article on this topic, we suggested that the term “progressive overload” is often misunderstood and that “progressive loading” is a more accurate and useful concept. Still, there’s more to discuss to provide true clarity on how to apply these principles to get the best results from your training.

The Origin of Progressive Overload

The term “progressive overload” is widely credited to Dr. Thomas DeLorme, an army physician in the 1940s 1. He was tasked with a practical problem: how to rehab his orthopedic patients faster to free up hospital beds. Necessity being the mother of invention, DeLorme’s approach was revolutionary at the time, especially in medicine.

Rather than light, high-rep exercise, he used progressively heavier weights to rehab his patients. There’s a story of his wife, Eleanor, coining the term “progressive overload” to describe his method in a way that wouldn’t alarm other doctors who would likely be skeptical of the term “heavy resistance exercise” that DeLorme used 1.

A notable case was Sergeant Walter Easley, who tore his ACL and MCL in both knees during a parachute jump. DeLorme had Easley use “iron boots,” a product from York Barbell, and perform 7 sets of 10 repetitions. Easley was instructed to increase the weight once he “mastered the weight for the 7 sets of 10.” This notion of increasing resistance only after demonstrated mastery and improved function is the critical original insight, later published in DeLorme’s 1951 book, Progressive Resistance Exercise: Technique and Medical Application 1.

The core idea from DeLorme was simple: gradually increase the resistance as the patient got stronger and more capable. This seems far removed from the overly complicated and sometimes contradictory definitions we see today.

What Progressive Overload Is (and Isn’t)

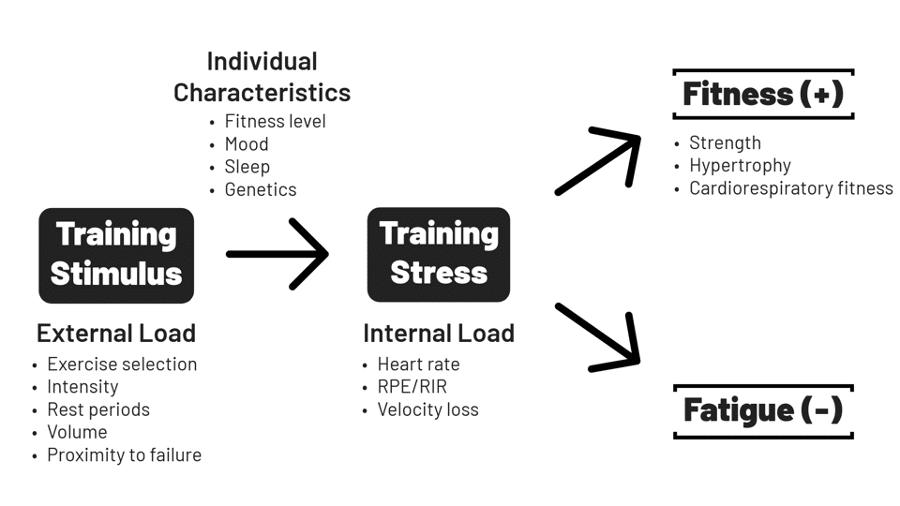

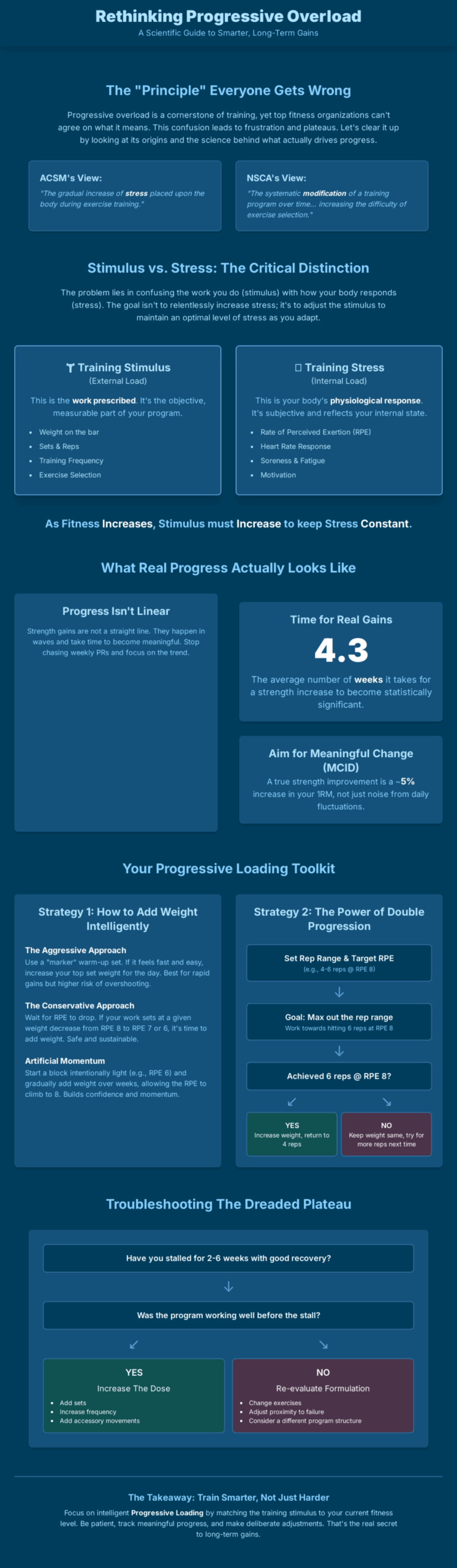

Many organizations like the ACSM and coaches define progressive overload as “the gradual increase of stress placed upon the body” 2. While this sounds right on the surface, it’s a poor definition because it confuses two critical, yet distinct, concepts: training stimulus and training stress.

- Training Stimulus (External Load): This is the physical work performed by the individual, i.e. what’s applied “externally”. In a training plan, it’s the weight on the bar, the specific number of reps, the total distance you run, or the total number of sets you perform. Think of this as the input variable you directly manipulate in your program.

- Training Stress (Internal Load): This is what’s going on inside the body in response to the training performed. Some of the psychological and physiological responses can be directly measured, e.g. changes in heart rate and heart rate recovery. Other internal processes are best assessed using proxies such as Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), subjective feelings of fatigue, soreness, and motivation, among others 3.

For completeness, the NSCA defines progressive overload as “the systematic modification of a training program over time… and increasing the difficulty of exercise selection” 4. Neither of these are consistent with the concept or implementation of progressive overload. Instead, the systemic modification of training over time is periodization, whereas exercise selection is a programming variable not directly related to altering training stress.

In any case, the biggest error when it comes to defining and understanding progressive overload is that it means an “increase in training stress”. It does not. Instead, the purpose of progressive overload is to maintain a similar, productive level of training stress over time to facilitate long-term adaptation. As your fitness improves (you get stronger or fitter), your body becomes more capable. Therefore, you need to apply a greater training stimulus (more weight/reps/sets) to elicit the same training stress you used to get from your training.

Conversely, if your fitness temporarily decreases (due to a lack of sleep, poor nutrition, or illness), you might need a lower training stimulus to produce the appropriate, more tolerable amount of stress.

The key insight is that training should not be a constant game of “how much more stress can I add?” but rather “how do I apply the right stimulus to maintain the correct amount of stress and keep making progress?” This dynamic, adaptable philosophy is the key to correctly implementing progressive overload.

Defining and Measuring Progress

So, if we aren’t just blindly adding weight, how do we know we’re progressing?

In resistance training, real progress is about demonstrating a higher level of performance under the same circumstances. For example, an improvement in strength could be an increase in the amount of weight lifted for a given number of reps, using the same range of motion and effort level. If an individual added 5-lbs to the bar, but squatted the reps high, that would not represent an increase in strength anymore than adding weight and the effort increasing markedly (e.g. from RPE 8 to 10).

We can refine our understanding of strength progress further by stealing a concept from medicine known as the Minimal Clinically Important Difference or MCID. For strength, the MCID is the amount of strength change that is large enough that it is unlikely to be due to mere measurement error or natural day-to-day fluctuations.

For example, we know that a tiny 0.5% increase in your 1RM (estimated or directly measured) is likely just noise, perhaps due to better sleep or motivation that day. A 10% improvement, however, is a clear sign of real, lasting muscular and neurological progress. We’ve found that a 5% change in strength likely is a reasonable MCID threshold. In other words, when strength performance goes up or down by ~5% or more, that’s likely real and not an artifact.

However, the time course for strength improvements that meet or exceed the MCID varies amongst individuals based on their training experience, response to a given program, how strength is assessed, and other factors like nutrition, sleep, motivation, to name a few.

Interestingly, research shows that strength gains are not linear and do not occur on timescale often described. A comprehensive review of 40 resistance-training studies found that, on average, it took 4.3 weeks for a demonstrable increase in strength to appear. The individual variation was large, with the range spanning from 1 to 12 weeks 5. Some of this variation is due to the variation in how individuals respond to a program, as well as the methods and frequency for assessing strength performance. Still, most people will not be able to improve strength every week, let alone every few days. Real strength gains take a bit longer to be developed.

There are some important implications of this finding both relating to mismatch between expectations and reality. By incorrectly assuming that progress should be made in a predictable, linear, and rapid manner, many lifters may be giving up on their programs too soon if they can’t add weight to the bar weekly (or faster). They assume that a plateau has been hit when in reality, they just need to stay the course until their gains are realized and become statistically significant. Additionally, attempting to add weight each week (or faster) is generally inconsistent with the time course of strength gains. Adding too much training stimulus can produce too much training stress and generate excess fatigue, which can overwhelm an individual’s recovery resources, leading to slowed progress and an increased risk of injury.

When and How-To Add Weight

The weight on the bar is simply a tool to stimulate the musculoskeletal and neuromuscular systems. Provided the weight is heavy enough to produce the desired adaptations, e.g. improved coordination and muscular force production, an individual is likely to get stronger so long as the dose (volume) of training is appropriate. For maximal strength, this generally means staying above ~70% of your 1RM 6 for multi-rep sets and 85% for single-rep sets 7 (which are more skill-focused).

This means that there is a relatively wide range of “viable” training intensities to improve strength, with similar results being generated by using loads contained therein. Practically speaking, we don’t have to add weight constantly to get stronger, but we do need to add it periodically to ensure we don’t fall “out” of the appropriate intensity range necessary for continued adaptation.

Here are three practical, coach-tested strategies for when and how to add load:

- The “Aggressive” Approach: Use a “marker” warm-up weight to gauge your readiness for the day. If that marker set feels lighter and faster than it did in the previous session, you have evidence that you can push the top sets heavier. This approach is most effective during periods of high resource availability (great sleep, solid nutrition, low life stress) and can allow an individual to demonstrate strength improvements as fast as they come online. However, because it relies heavily on day-to-day fluctuations, it also carries a higher risk of overshooting your actual capacity and prematurely accumulating unwanted fatigue if you get it wrong, potentially leading to an eventual abrupt plateau.

- The “Conservative” Approach: Wait for a noticeable, sustained decrease in your Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) before increasing the weight. For example, if your sets of 5 have been consistently feeling like an RPE 8 (2 reps left in the tank), wait until they drop to an RPE 7 or RPE 6 for the same weight before increasing the load by a standard increment (e.g., 5 lbs). This is a reliable method that prevents overshooting the target RPE, which can be useful for individuals who are prone to going too heavy, too often. On the other hand, it may feel frustratingly slow for some driven athletes.

- The “Artificial Momentum” Approach: Start with a weight that is intentionally light (e.g., aiming for an initial RPE 6) and gradually increase the load over a training block (4-6 weeks) so that the same prescribed work (e.g., 5 reps) becomes progressively more challenging (e.g., reaching RPE 8 by the end of the block). This provides a predictable on-ramp and may offer a strong psychological boost from adding weight week-to-week, even if the actual strength gains aren’t occurring at the same rate in which weight is added. With this setup, the final week of the block can serve as an implicit test of progress as compared to previous training cycles.

Although slightly different in execution, each strategy attempts to maintain the correct level of training stress in order to produce the desired fitness adaptations.

The Power of Double Progression

One programming option that may make it easier to correctly implement progressive overload is double progression, which combines the manipulation of both reps and load for improving muscular adaptations 8. This approach offers more flexibility to take advantage of whatever strength adaptation is available—either strength endurance (more reps) or maximal strength (more load)—and helps build momentum by providing a clear, short-term goal for every training session.

For example, you might be programmed to perform a set of squats for “4 to 6 reps at RPE 8.”In this scenario, you’re aiming to reach the top of the rep range (6 reps) at the prescribed effort level (RPE 8) before increasing the weight. This provides a built-in “runway” for strength adaptations to occur. Once you successfully hit your target of 6 reps at RPE 8, you increase the load and reset the goal back to at least 4 reps at the new, heavier weight. After building some capacity, it is unlikely the individual will “fall out” of the prescribed rep range with the new, heavier weight.

Using this approach his method can be superior to fixed-rep approaches, especially when dealing with exercises where the load jumps are large, e.g. dumbbell, unilateral, and/or machine work.

Troubleshooting the Plateau

Even with a perfectly executed progressive overload strategy, plateaus will happen. We define a plateau as an arbitrary line where a coach would say, “you haven’t seen a demonstrable improvement in a while.” For a relatively untrained individual, this might be 2-3 weeks. For a highly trained lifter, it could be extended to 5-6 weeks. Continuing a program beyond these timeframes without any improvement increases the likelihood of reduced long-term progress, whereas shortening the timeframe can lead to unnecessary program-hopping.

When a plateau hits, your first step is a simple assessment of recent training history and environment:

- Was the program working well before tapering off? If so, you likely need to increase the training dose. This means increasing volume (adding more sets) via increased training frequency (adding sessions) and/or more exercises for a specific movement pattern, while keeping the average intensity and proximity to failure about the same. You’re simply increasing the total training load in order to increase training stress back to a productive level.

- Was the program not working well from the start? In this case, both the training dose and the program’s formulation are on the table. You must check the environmental inputs first: Are they sleeping well? Is nutrition adequate? If environmental inputs are poor, consider lowering the training load while maintaining the formulation (a small deload is often warranted here). If the environment is mostly fine, consider adding training load while simultaneously reformulating the program, e.g. swapping the exercises, adjusting the RPE targets, or shifting the focus of the rep ranges to better target the desired adaptation.

Remember, every program eventually needs to be adjusted over time. The key is knowing how and when to make the correct changes for the individual. For more on troubleshooting plateaus, check out the 100+ page ebook on programming that accompanies the Low Fatigue Template.

Final Takeaway

Overall, the foundational exercise concept of progressive overload is often misunderstood and poorly defined, leading to suboptimal results and premature plateaus. To correctly implement progressive overload, we recommend keeping the following points in mind:

- Increases in strength allow you to progress. As an individual gets fitter, a greater stimulus (more weight/reps) is needed to produce the same stress and continue making progress. If fitness decreases, a lower stimulus would be needed.

- Strength performance varies day-to-day. Depending on biological, psychological, and environmental inputs, strength ebbs and flows between a “floor” and a “ceiling”, creating an average strength level.

- Strength gains are not linear. Strength adaptations occur due via updates to both muscular (hardware) and neurological (software) systems over time. With intelligent programming and continued training, an individual’s average floor, ceiling, and average strength should increase over time.

- Plateaus are common, but interpreting them can be tricky. Plateaus in training represent a state where demonstrable progress has not been seen after an extended amount of time. Determining whether the plateau is due to too much training stress or not enough requires a deeper investigation relating to recovery, previous success (or not) with the program, and the individual’s experience.

Thanks for reading. See you in the gym!

References

- Todd, Janice S et al. “Thomas L. DeLorme and the science of progressive resistance exercise.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 26,11 (2012): 2913-23. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825adcb4

- American College of Sports Medicine. “American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 41,3 (2009): 687-708. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

- Impellizzeri, Franco M et al. “Internal and External Training Load: 15 Years On.” International journal of sports physiology and performance vol. 14,2 (2019): 270-273. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0935

- National Strength and Conditioning Association. Foundations of Fitness Programming. National Strength and Conditioning Association, 2015.

- Lambrianides, Yiannis; Epro, Gaspar; Smith, Kenton; Mileva, Katya N.; James, Darren; Karamanidis, Kiros. Impact of Different Mechanical and Metabolic Stimuli on the Temporal Dynamics of Muscle Strength Adaptation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 36(11):p 3246-3255, November 2022. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004300

- Schoenfeld, Brad J et al. “Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations Between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 31,12 (2017): 3508-3523. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002200

- Androulakis-Korakakis, Patroklos et al. “Reduced Volume ‘Daily Max’ Training Compared to Higher Volume Periodized Training in Powerlifters Preparing for Competition-A Pilot Study.” Sports (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 6,3 86. 29 Aug. 2018, doi:10.3390/sports6030086

- Plotkin, Daniel et al. “Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations.” PeerJ vol. 10 e14142. 30 Sep. 2022, doi:10.7717/peerj.14142